-------------------------------------

Where are the Latino Legends in Baseball?

Article by:

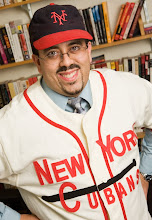

Called a must-read by Slate Magazine and the San Franciso Chronicle, Adrian Burgos’ Jr. recent book, “Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line,” examines an era in baseball history largely ignored by historians and sports fans until now: Latinos in professional baseball pre-1947. Burgos, an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Illinois, has long been an expert on the Latino struggle for acceptance both in the major and Negro leagues, serving on the screening and voting committees for the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2006 special election on the Negro Leagues. Latin Week sat down to talk with Burgos about how Latinos helped break the color line in baseball long before Jackie Robinson, and how Latinos still face a fight for respect on the field today.

Not a single Latin American was voted to the all-century team? Does that still hurt?

The absence of Roberto Clemente from the all-century team is a major issue on several levels… Whether Clemente is the greatest outfielder or rightfielder in baseball history is a debatable matter, but whether he is one of the most important baseball figures of the 20th century is without debate. An all-century team without Clemente and all he represented to the game’s history is just not right. The fact that Major League Baseball (MLB) had the discretion to address this oversight and opted not to is telling of the need for an understanding of baseball history through a Latino framework.

Focusing on the book, one thing people are not aware is that there were Latinos playing baseball long before Jackie Robinson. Why we are not given the credit for opening the doors for other peoples of color?

The full story of Latinos in U.S. professional baseball is unknown to the American baseball public. Many do not know that over fifty foreign-born and US-born Latinos performed in the majors from the 1880s through 1947, when Jackie Robinson began the dismantling of organized baseball’s color line. Fewer realize that the overwhelming majority of Latinos who played in the States during the era of baseball’s segregation performed in the Negro leagues, over 250 Latinos played in the Black baseball circuit starting in 1900.

In “Playing America’s Game,” I argue that the manner that major league team officials manipulated racial understandings served as a template for how Branch Rickey would approach the official launch of the racial integration of Major League Baseball… officials for teams such as the Cincinnati Reds, Boston Braves, New York Giants, and, most notably, Washington Senators, brokered access for lighter-skinned Latinos in the 1900s and by the mid-1930s began to allow increasingly darker, more racially ambiguous Latino players into the Majors. However, these Latino players were not given the same exact treatment as Jackie Robinson did, because these officials were not engaged in trying to overturn the color line system of racial division, but rather to manipulate it for their own gain—signing talented Latino players for lower salaries than what they would earn if they were white Americans.

In your book you describe the many obstacles Latino ballplayers had to face, for example speaking English. Do they still face these problems?

Learning to navigate the English-language press remains an extremely challenging obstacle once they “make it” in the United States. It is in the press coverage of Latinos we continue to see how Latino difference as racial beings constantly in production. For example, during last year’s American League Divisional Series Manny Ramirez became embroiled in a controversy after stating that he was not worried whether the Red Sox would defeat Cleveland, because his team had been down before and had overcome a 3-game-to-none deficit in defeating the New York Yankees a few years earlier. Some stated this was another example of “Manny being Manny,” but what really perturbed me was hearing a prominent ESPN reporter stating that Manny did not know what he was saying because he lacked mastery over the English language. What?! Manny came over from the Dominican Republic at ten years old and was schooled in the United States before graduating from George Washington High School in Washington Heights (NYC). But this reporter lumped all Latinos into a familiar stereotype, and then he used that to frame his analysis. And thus continues a practice of portraying Latino players as ignorant, dumb, or not as smart as the white American player, a practice that dates back to the earliest era of Latino participation in organized baseball.

The New York Cubans [a team of Latino players that competed in the Negro leagues] won the Negro League Championship in 1947. There is hardly any talk about this team [in popular and official histories of baseball] – why?

The NY Cubans were one of three NYC-based teams to enjoy a banner season in 1947, and yes, they are the least discussed in part because the other two were the Brooklyn Dodgers and NY Yankees. So there is the issue of timing. The NY Cubans enjoyed their greatest success in the Negro Leagues during the same year that Jackie Robinson initiated the dismantling of organized baseball’s color line system.

Another part of the reason the Cubans team suffers today from a lack of attention is the misperception that they were not a significant team in the Negro Leagues or in New York. Much to the contrary, a look at two main Black weeklies published in NYC (The New York Age and Amsterdam News) one sees that the Cubans and not the NY Black Yankees were celebrated as “Harlem’s Own”…

Much of the story of Black baseball is told as just that of African Americans, leaving out the Latinos who participated in the Negro Leagues from its inception … Moreover, the NY Cubans (and its predecessor the Cuban Stars) were trailblazers in bringing in talent from throughout the Americas. While operating these teams, Alex Pompez introduced the first Dominican, Puerto Rican, and Panamanian players to play in either the Negro Leagues or the Majors. The NY Cubans represent a vital part of baseball history in the Americas for they offer a different approach to diversity in U.S. professional baseball long before “Los Mets.”

One player on the team you talk about highly is Martin Dihigo. Many former Negro League Players say he was the best!

Dihigo is quite a unique figure in the annals of baseball history because he was an ace pitcher and a fabulous everyday player (and a pretty good team manager on top of that). Think of someone who was on a Hall of Fame level as a pitcher in Black baseball (the Smokey Joe Williams, Jose Mendez, and Satchel Paige type pitchers) and then think of the very best everyday players from the Negro Leagues. Put that together and you begin to imagine El Maestro, El Inmortal, Martin Dihigo.

Should Roberto Clemente’s number (21) be retired?

I am of two minds on this question. For one, I want Latino players to be a living memorial to the meaning and significance of Clemente to all Latinos. The best memorial is seeing a great Latino player chose to take the number 21, and demonstrate mastery on the field and also grace, dignity, and a willingness to speak for the cause of social justice off the field…

No greater example has been set for all of those involved in any capacity within organized baseball than what Clemente did… How best do we recognize that vital historical lesson? I am for a living memorial, the Latino players keeping his (and our) story on the field for all to see.

http://www.latinweekny.com/?c=118&a=1488