From time to time I will provide a "retro post," pieces I have posted elsewhere before starting this blog. Here is a piece on the commemoration of Jackie Robinson Day and how baseball's other integration pioneers who followed in his stead are given short shrift.

-------------------------

On April 15, Major League Baseball (MLB) again celebrated its integration pioneer Jackie Robinson by allowing players to wear his retired jersey number in honor of his legacy. All the black players donning 42 spurred lamentations in the media about the decline numbers of African Americans in baseball.As African American numbers have declined, Latino numbers have skyrocketed, with many darker-skinned players from Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Cuba and Venezuela owing thanks to Jackie's door-opening achievement. Little is said about why darker-skinned Latinos aren't so inclined to don 42, because so little is understood about how they relate to baseball's integration story.

The truth is, a major piece of the Robinson legacy is missing and MLB is blowing an opportunity to educate the American public about integration's full scope.

Latinos were drastically affected by segregation. While a select number of Latinos (just over 50) performed in the Majors before Robinson, over 230 played in the Negro Leagues, just as Robinson did before organized baseball's color line was dismantled.

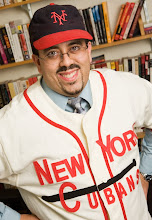

The process wherein the overwhelming majority of Latinos were designated racially unacceptable for organized baseball remains one of baseball's lesser known stories. As I argue in my book Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line (University of California Press, 2007), Major League team officials masterfully manipulated racial understandings throughout the time its color line stood in place to broker access for a few Latinos. Over time the Latinos officials ushered into organized baseball became increasingly racially ambiguous. "He's not black," they explained, "He's Cuban." Thus the Washington Senators, Cincinnati Reds, New York Giants, and a handful of other organizations plucked players from the Spanish-speaking Americas. They so successfully muddled racial perception that it necessitated an unambiguously black player to destroy any semblance of ambiguity, enter Jackie Robinson.

It is extremely troubling that this history continues to be conveniently elided in the Robinson commemorations and the more recently instituted Civil Rights Game. For this year's game MLB convened a panel of seven African Americans and Mets GM Omar Minaya as the lone Latino to discuss baseball, race, and civil rights. The lineup of luminaries gathered reveals that MLB does not acknowledge Latino participation in the struggle to overturn segregation or their stake in the past, present, and future of baseball.

That this continues to occur at the moment when Latinos are nearing forty percent of Major Leaguers is shameful and contributes to the popular perception of Latinos as a people without a (long) history in America's game--although the first Latino played in the National League in 1882.

The way MLB (mis-)remembers Jackie and baseball integration also diminishes the legacy of the Negro Leagues and of the integrated Latin American leagues.

On the other side of organized baseball's racial divide African Americans and Latinos collaborated in the establishment of a circuit that for decades refined the ball-playing skills of the excluded. In Havana, Santo Domingo, San Juan, Mexico City, and Caracas, among other Latin American cities, African American players like Rube Foster, John Henry "Pop" Lloyd, and Willie Wells were welcomed in racially integrated leagues. Drawing on his own experience, Foster's vision for the Negro Leagues from his various failed start-ups until he successfully launched the Negro National League in 1920 always included Latinos.

Jackie Robinson was a product of the circuit they built. And let's not forget that it was in this circuit the multitalented athlete honed his skills in what was arguably his fourth best sport. And it was here where Branch Rickey and his men first scouted pioneering black players Robinson, Monte Irvin, Roy Campanella, and Orestes "Minnie" Minoso, among others.

For all the recent talk about engaging in a national conversation on race, we are constantly revisiting a narrative of race relations of black-white, whether inside or outside of baseball. That circumscribed narrative about race fails us all.

2009 will mark the 60th anniversary of Minnie Minoso's debut as the first black Latino to perform in the Majors. His pioneering achievement in overcoming a doubly complex set of racial and cultural challenges as a black Latino to develop into a major league star ought to be the centerpiece of a year-long series of events that portrays baseball's integration saga in its full multicultural splendor. Only then will we truly remember the full impact of Jackie's achievement and honor the entire roster of those who contributed to the overthrow of baseball's Jim Crow system.

Posted: April 18, 2008, http://www.baseballmusings.com/archives/025991.php

Sunday, July 13, 2008

Retro Post: On Remembering Jackie Robinson and Baseball Integration

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Thanks for sharing a tremendous post. I would like to share some interesting website that one http://www.yourbaseballbat.com/

Post a Comment